Just as X marks the spot for any treasure, X also marks the makhraj (point of articulation) for the Arabic letters!

Makhaarij Al-Huroof [1] translates to “the points of articulation for [the Arabic] letters”. It is imperative that one learns and correctly pronounces the Arabic letters in order to read tajweed with precision. Colloquial dialects differ greatly, so as an Arabic speaking person, I can only stress the importance of learning the makhaarij. They are the very nectar of tajweed, and I can only hope that in my humble attempt to put forward the rules, you can achieve a great understanding.

The area of speech has been divided into five parts, and subdivided into 17. The first five divisions are as follows:

| Al-Jawf | The Interior/Chest Area |

| Al-Halq | The Throat |

| Al-Lisaan | The Tongue |

| Al-Shafataan | The Lips |

| Al-Khayshoom | The Nasal Passage |

This post will look into the first of these categories: Al-Jawf.

![]()

Al-Jawf [2] (The Interior/Chest Area)

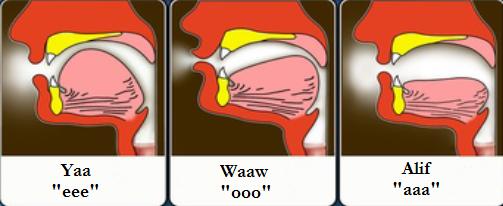

The interior comprises of the inner, open area of the mouth, behind the meeting point of the lower jaw and top teeth. This area is an “estimated” makhraj (point of articulation), all other makhaarij are “actual” as they apply to constant sounds and have been pinpointed with accuracy. From the jawf three letters emerge. These are the:

alif ( ا ) preceded by a fat-ha, pronounced “aaa”

yaa ( ي ) preceded by a kasra, pronounced “eee”

waaw ( و ) preceded by a dammah, pronounced “ooo”

![]()

These three letters are usually called Huroof Al-Maddeeyah[3] (or as I call them, madd letters). They may also be called Huroof Al-Jawfeeyah[4], as they emerge from the jawf.

To better understand the makhraj of these letters, it is essential that we see the shape of the tongue and lips. This is illustrated in the following diagram:

![]()

Here we can compare the difference of the three positions of the tongue. The alif corresponds to the pale pink tongue, waaw to the hot pink tongue, and yaa to the red tongue:

![]()

As with any language, it’s is best to listen and repeat after a teacher or sheikh to ensure you are sounding the letters in the correct manner; after all, no written or drawn aid can give the required accuracy for tajweed.

As a final note, there are two important things to mention in regards to makhaarij al-huroof.

First, to figure out the makhraj of a letter, pronounce it with a sukoon, preceded by a fat-ha. Examples,

![]()

أدْ أعْ أتْ أشْ أضْ

![]()

Second, note there are 28 letters in the Arabic alphabet, however, there are 31 huroof al-tajweed (tajweed letters). The extra letters are hamzah, consonant yaa’, and consonant waaw. These will be looked at in greater detail throughout the upcoming posts.

![]()

Resources Link:

– Makhaarij Al-Huroof document

![]()

Note, this document is found on the resources page.

![]()

Related Posts: Makhraj Al-Halq – Makhraj Al-Lisaan – Makhraj Al-Lisaan Pt 2 – Makhraj: Al-Shafataan – Makhraj: Al-Khayshoom

![]()

[1]مخارج الحروف

[2]الجوف

[3]حروف المدية

[4]حروف الجوفية