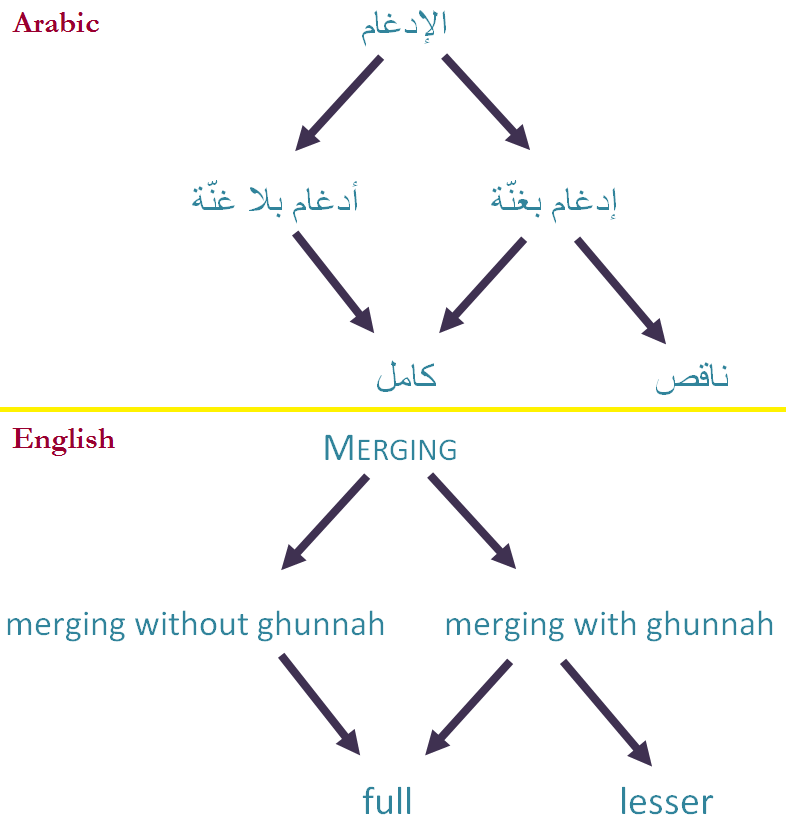

Merging two similar things is something we do all the time. We do this when we categorise objects with similar characteristics (using the dominant characteristic as the go-to label) because it’s easier for us in the end to pull out what we need. Similarly, it’s easier for the tongue to merge two letters, and sound out the one with the more dominant characteristic. This ruling is called idghaam.

Idghaam Al-‘aam: the common/general idghaam is to sound the first of two letters as the second – sounding the two letters as one letter with a shaddah on it. This common idghaam has two branches: kabeer (large) and sagheer (small).

Al-Idghaam Al-kabeer: occurs when a voweled letter precedes another voweled letter such that they become one letter with a shaddah on it.

Al-Idghaam Al-sagheer: occurs when a saakin letter precedes a voweled letter, such that they become one letter with a shaddah on it. Al-idghaam al-sagheer has three categories, these are

Mutamaathil – Mutajaanis – Mutaqaarib

We will study these in greater detail. First let’s look at Al-idghaam al-kabeer.

![]()

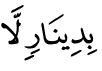

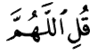

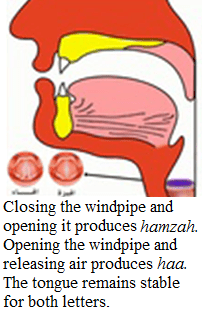

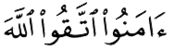

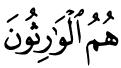

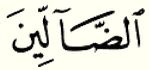

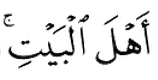

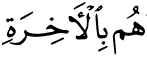

Al-idghaam al-kabeer occurs only when two of the same letters meet within a word – both letters are voweled, and therefore must be said as one letter with a shaddah on it.

Examples of this idghaam are as follows:

la ta’mannaa – originally ( تأمنُنَا )

ma makannee – originally ( مكنَنِي )

ta’muroonnee – originally ( تأمرونَنِي )

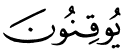

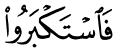

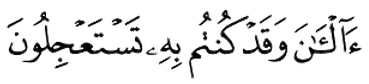

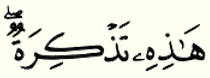

![]()

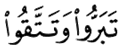

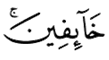

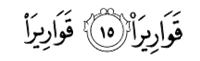

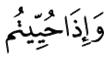

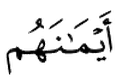

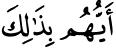

Let’s note the first example also involves a tajweed rule, Ishmaam. I haven’t covered this yet, and will do soon, insha Allah. What we should focus on now though, is merging the two letters, sounding a shaddah, and by principle, a ghunnah.

![]()

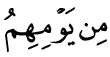

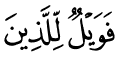

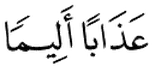

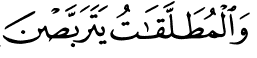

Al-idghaam al-sagheer happens when a voweled letter follows a saakin letter. This idghaam is under three categories. These categories define when an idghaam sagheer occurs. They are:

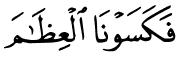

Mutamaathil: when the letters being merged come from the same makhraj (point of articulation), and have the same sifah (characteristic). Examples:

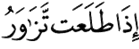

Ithaa tala‘at tazaawaru

Ith-thahaba

Ith-hab bikitaabee

Yudrikkum

Qul laa

Falaa yusrif fil-qatl

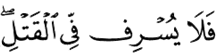

Jaa’akum maw’ithatun Lan nasbira

Lan nasbira

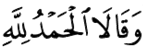

‘Afaw wa qaaloo

Note: the last example happens on a consonant waaw. If the first word ends in a waaw or yaa’ maddeeyah, then this ruling does not apply, and a shaddah must not be sounded on the second waaw/yaa.

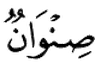

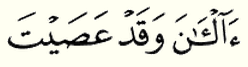

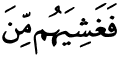

![]()

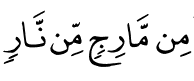

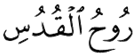

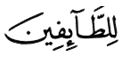

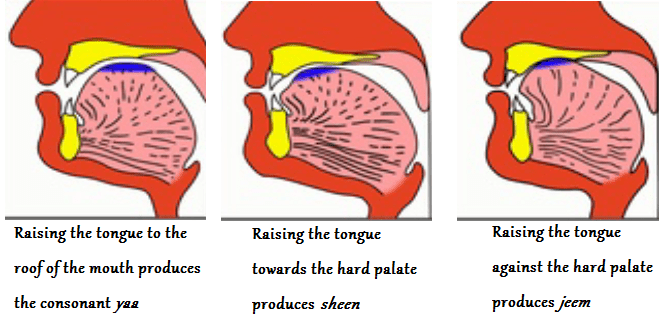

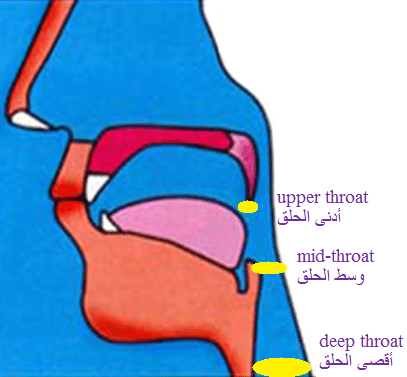

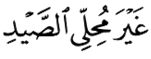

Mutaqaarib: when the letters being merged come from two makhaarij – close in proximity, and have different (but similar) sifaat. Examples:

The letter qaaf and kaaf

The letter laam and raa’

The letter noon with the letters waaw, yaa’, raa’, meem, laam ( و يرمل from the noon saakinah ruling)

![]()

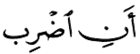

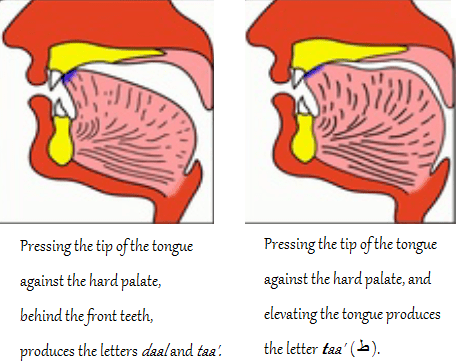

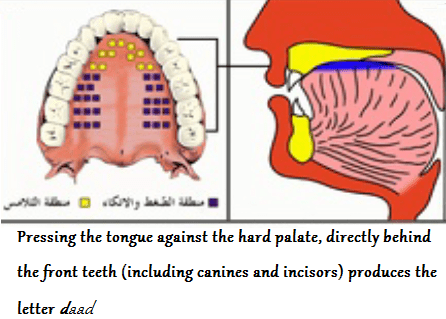

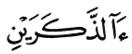

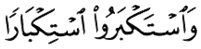

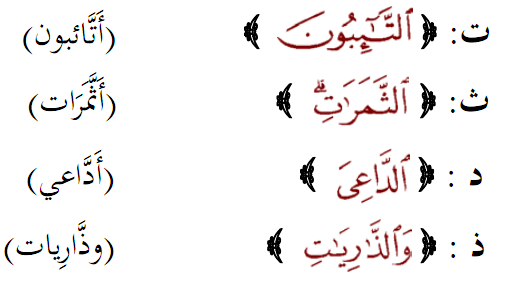

Mutajaanis: when the letters being merged come from the same makhraj, but have different sifaat. This occurs for the nat‘eeyah, lathaweeyah and shafaweeyah letters.

The nat‘eeyah letters:

– merging happens to the taa’ ت and taa’ ط and vice versa

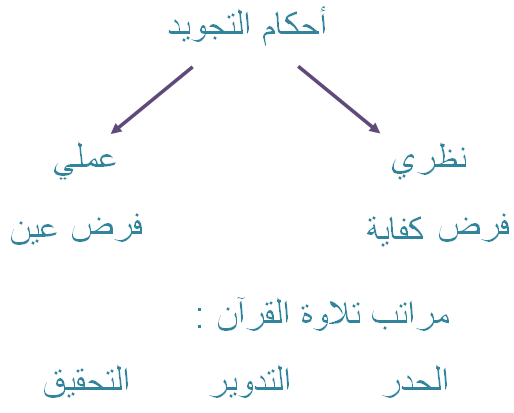

waddat taa’ifatun (read: ودطّائفة )

waddat taa’ifatun (read: ودطّائفة )

– merging happens to the taa’ ت and daal د and vice versa

athqalad-da’awaa (read: أثقلدَّعَوَا )

athqalad-da’awaa (read: أثقلدَّعَوَا )

qat-tabayyana (read: قتَّبَيَّنَ )

Note, the first example has a little ط in it. This is because the tongue should be pushed up completely against the hard palate as though you are going to pronounce the taa’ – however it should not be sounded.

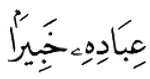

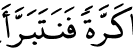

![]()

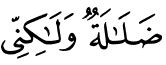

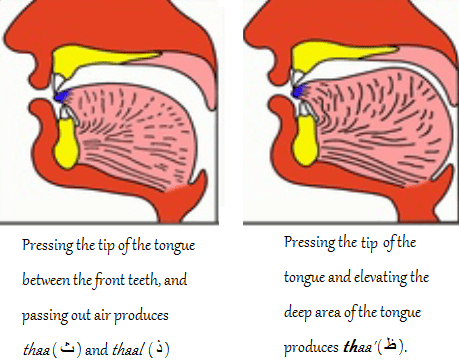

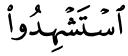

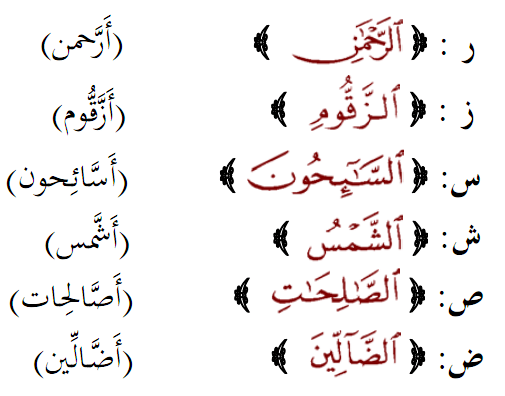

The lathaweeyah letters:

– merging happens to the thaa’ ث and thaal ذ

yalhath-thaalika (read: يلهذّلك )

– merging happens to the thaal ذ and thaa’ ظ

Ith-thalamoo (read: إظَّلموا )

Ith-thalamoo (read: إظَّلموا )

![]()

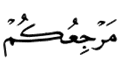

The shafaweeyah letters:

– merging happens to the baa’ ب and meem م

Irkamma‘anaa (read: اركمَّعنا )

![]()

This wraps it up for the idghaam ruling. Keep in mind that there is idghaam for the noon and meem saakinah rules. And idghaam kaamel and naaqis for the noon saakinah rulings in particular.

Resources link:

–Idghaam [Tajweed Basics: Foundations and More: page 12]

There is a big contradiction between the way I type transliteration, and this post. You will come to realise this as I begin to explain this rule.

There is a big contradiction between the way I type transliteration, and this post. You will come to realise this as I begin to explain this rule.

_______

_______

_______

_______

____

____ ____

____

_____

_____ _____

_____ _____

_____ _____

_____

_____

_____ _____

_____ _____

_____ _____

_____